2024年11月14日

2024 CUHK Anthropology Department Summer Fieldtrip

Berlin, Germany

29 May – 6 June 2024

Tim Rosenkranz: In May/June 2024 we went on our Anthropological Field Seminar to Berlin. We were a very eclectic group of first and final year undergraduates, MA students and myself, a German emigrant and frequent visitor of Berlin. Embracing our positions as visitors, strangers, tourists, and students, we explored every day a different aspect of our theme “city in transition”: migration, tourism, memory, divide and reunification, political regime change, gentrification, art and freedom, religion, sexuality and gender. The program was intendedly open, facilitating every day some encounters with locals, scholars, tour guides, and different communities but also leaving ample time and space for the students to explore and roam the city by day and night following their own interests!

During our visit, students kept a personal field journal in writing, pictures and video, sharing every day some of their experiences and observations with the group. Below we offer you some glimpses into our days in Berlin through some of the student’s shared posts and reflections as well as some of my photographs and introductions.

Day 1: Arrival

Tim: Our arrival day was mostly settling in. The students learned to navigate the tram and subway system and we had two German meals (very heavy, mostly meat and potatoes!). Everybody was quite tired from flying but enthusiastic and ventured around the Mitte district to explore our neighborhood.

Lunch for the early arrivals, our first German meal.

Sze Man: We accidentally set foot in the field of the radical playground project because of the rain. The project presents the history of playgrounds in Germany and the evolution of playground settings. No kids are playing in the space due to the rain and dampened floor; instead, the side of the playground has a bustling and hustling corner serving a bunch of people with a couple of tables and chairs and food provided by the food car people. It makes me think of the multiple uses and mobility of public space. A playground is a place for kids, but the place can change its original functions with regard to the situation. People came to the playground to take shelter from the rain due to the design of the playground. It has a two-story building inside the playground, and the first floor can protect people from the sun and rain. A part of the playground was activated to serve the citizens when the circumstances changed. The question is, when planning a place for doing something, should we only satisfy the target user for the place, or should we consider many stakeholders who may benefit from the space? Maybe it does not matter how to plan at the beginning as long as the flexibility of the place is kept (e.g., remaining more empty space), then people can make their own use for what they want to do.

First group dinner, German food near Museums Island.

Day 2: Guided Walking Tour of Main Sights in Berlin-Mitte

Tim: We went on a typical ‘highlight’ tour in Belin’s historic Mitte district. It turns out that most tourist sights here are planned or coincidental memorials for some kind of atrocity or triumph of the past, posing question and tensions about: Individual experience and mass tourism, the commodification of tragedy, as well as the performance of identity through memory politics in Berlin.

Walking through the Brandenburg Gate: Formerly borderland, now a tourist site.

Lunar: While we circled around the tour guide and listened to her story-telling, I noticed that there were several other tour groups nearby, esp. in some popular tourist spots like the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. I suddenly realised how the past of Germany and Berlin were being re-told and re-constructed again and again every day in front of the tourists. What the tourists are curious to learn and expect to hear, in a way, shape how the history is presented. And although it is good to try to learn from the past and avoid repeating the mistakes, these “mistakes” of Germany/Berlin history seem to be re-packaged into commercial products for tourists from worldwide to consume.

The ‘stumble stones’: Remembering former residents who became victims of the Holocaust.

Hui: We walked along the roads from the Topography of Terror to the nearest S-bahn station “Anhalter Bahnhof”, and we discovered this building. We were attracted because it looks so grand and historical from a distance, yet there were almost no tourists in the surroundings.

Not until we walked nearer, seeing the information on google maps comment and the two information boards next to it, we could hardly find out it was the Anhalter Bahnhof, which was one of the most important railway station in Berlin before WWII, but it was bombed during WWII and only the main entrances were left. This abandoned building was also known as a starting point for many people fleeing Germany after 1933 and for its usage by the Nazis to deport elder Jewish citizen to the ghetto camp of Theresienstadt. However, it was not under maintenance, which is very different from the beautiful tourist spots and museums that we saw earlier in the guided tour. This is obviously a historical place that recorded an important part of history of Berlin and Germany, just as other spots do, but why is here being neglected?

After some searching online, I found out that the Stiftung Exilmuseum planned to build a museum about the Anhalter Bahnhof by 2028. This makes me wonder: There are 170 museums in berlin, who built them and for what reasons were they built? What are the factors affecting the construction of what is worth being remembered?

Dark skies above “The Memorial of the Murdered Jews of Europe’.

Day 3: Jewish Museum and Chinese Community

Tim: We went to the Jewish Museum. It was as overwhelming as impressive. Many students got to know for the first time the centuries of Jewish peoples’ lives in Europe/Germany, the long process of othering and the contemporary questions of belonging (who am I)?

Dr. Jingyang Yu tells students about her research about Chinese immigrants to Berlin.

In the afternoon we met local-Chinese researcher Jingyang Yu, who told us about the history of Chinese migration to Germany in front of Berlin’s largest Chinese community church. She explained how second generation migrants in Berlin are challenging their parents’ insistence on language and identification (“Why do I need to learn Chinese? Am I Chinese?”). She further explained the role of church networks for new migrants and took us to a nearby Chinese restaurants for a HK-style feast. Lap Yan went to talk to the restaurant’s owner, noticing how his story and ideas resembled his own grandfather’s, who migrated from Shanghai to Hong Kong.

A Chinese feast in Berlin with Jingyang.

Hok Nga: The whole quote [by Gabriel Riesner, 1831, displayed in the Jewish Museum] is: “We are not immigrants; we are native born. And, since that is the case, we have no claim to a home anywhere else. We are either German or we are homeless.” When I saw this quote, I think of the Jews who were born in Germany could claim that they were native but not immigrants, which led to the issue of identity. They were born in Germany but their ethnicity was Jews, which kind of created a dilemma between the two identities. It is interesting to know more about how Jews, especially the second generation, think of their identity just like the second generation of Chinese immigrants in Germany mentioned by Jingyang. Is it possible to have the two identities at the same time? If yes, how?

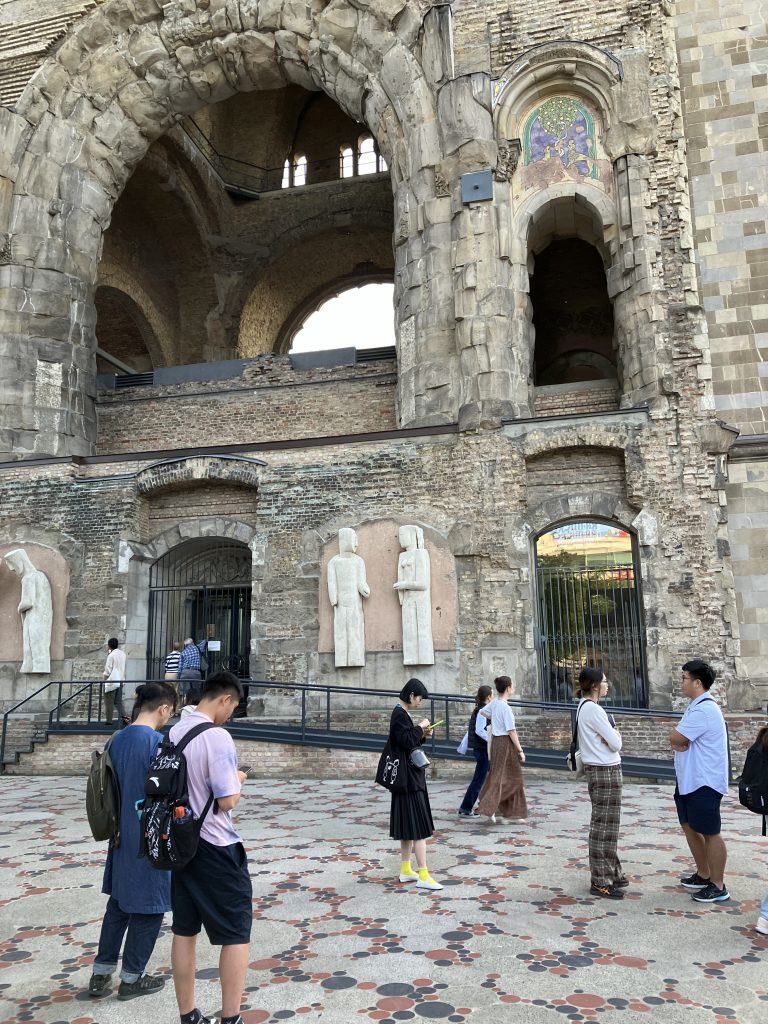

An evening stroll to Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, destroyed in WWII and never rebuilt.

Day 4: Jewish Community and Renter’s Protest

Kim Chi: We visited the Fraenkelufer Synagogue in Berlin, the first active synagogue in the city after WWII. Stepping inside, we saw the synagogue’s architecture and sacred symbols, which carried deep meaning. It reminded us of the resilience and faith of the Jewish community. Meeting community members and activist Nirit Bialer, we had meaningful conversations about the challenges they face and the ongoing work to preserve Jewish culture in Berlin. Reflecting on our visit, arise important questions. How does one rebuild and revive a religious institution after such devastating events? How can we honor the past while creating spaces for hope and connection? This visit underscored the significance of cultural preservation and interfaith dialogue.

Students in the community hall of Fraenkelufer Synagogue.

Yvonne: Our visit at the Fraenkelufer synagogue was guided by Nirit and Dekel who have been born and raised in Israel. Nirit migrated to Berlin 15 years ago. Nirit told us that she didn’t give much thought of her own identity of being a Jewish until she started living in Berlin. Being foreign in the city, Nirit found that the synagogue, a place where people who practice Judaism pray and meet a rabbi, serves more than a place for religious ceremonies but the cultural spot that connects the Jewish in the city. Similar to the Chinese Christian community who serve the Chinese immigrants, the Jewish synagogue is essential to the new comers to the city. A religious venue could serve different purposes under this context.

Alex talks to Nirit Bialer in the synagogue.

Sze Wing: The rent protest showed me Berliner’s passion for political participation. The activists emphasized that the “rent problem” is a global issue, and what they can do is to strive for the basic human right — living. Similar to the household registration system in China, refugees and immigrants at least have to find the place to settle their living so it is a great timing to consider how the rent problem affects all the people.

Is housing a right or a commodity: Students meet protestors in Berlin.

Zhiyuan: After a long walk and commute, we managed to catch the tail end of the renters’ protest, while some classmates departed to pursue their own interests. Demonstrations are always an exciting activity for me, regardless of the agenda being proposed by the community, so witnessing these events is always a compelling factor in deciding where to go. This time, however, I was completely an outsider in terms of the direct interests of the protesting community. It was still quite moving to see the creative signs and expressive slogans displayed—”Berlin is our city, too”. There was a festive atmosphere that came with the food vendors, people sitting on the ground drinking beers, and cheers for speeches.

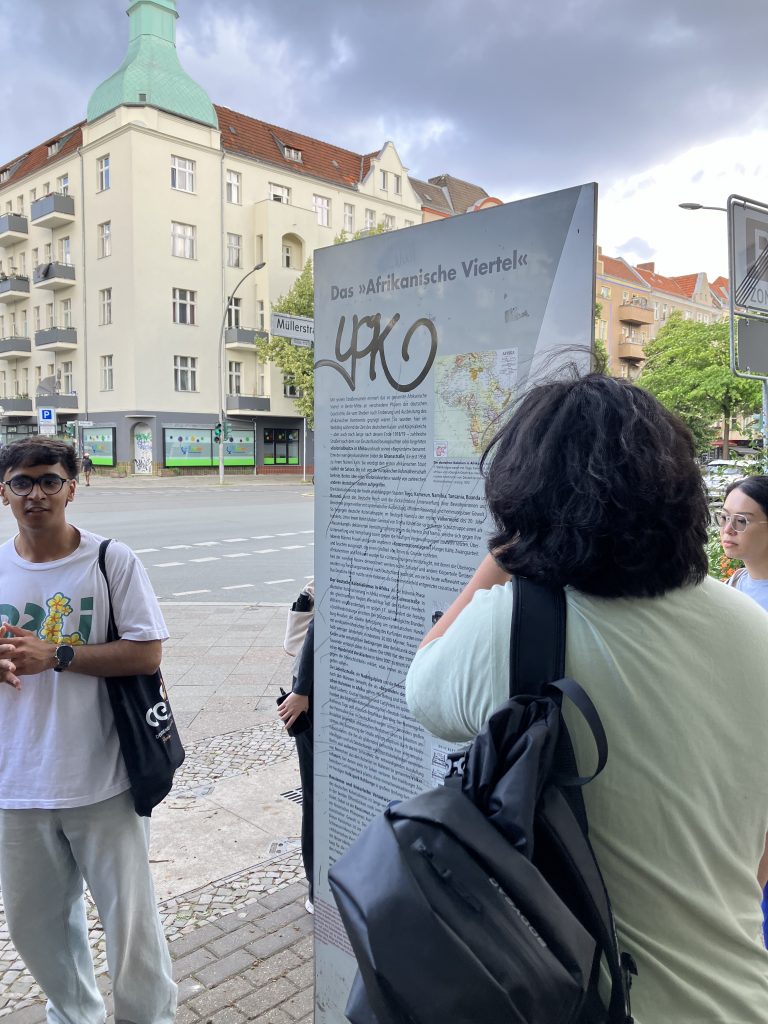

Day 5: Decolonial Berlin

Tim: We met our guide of the “Decolonial Tour” in the “Afrikanisches Viertel” which is a “normal” living quarter in the Wedding area of Berlin with many housing estates, allotment gardens and very few shops. The students seemed confused about why we were there, until our guide pointed out all the ‘African’ street names and their history: All these names were places colonized by Germany in Africa in the 19th century, some streets still had the names of infamous and cruel colonizers, while a few had changed to commemorate people from these places fighting colonialism. We talked a lot about the slow process of making colonial history explicit and contesting its silent persistence, and the politics of naming. The allotment gardens (small plots of recreational land) in the area themselves are named as colonies, a way of normalizing colonialism. It was a quite dense and eye-opening experience of everyday colonial presence and persistence.

The “African District” in Berlin, confronting colonialism and its continuities.

Hei Man: Today, our visit to “Little Africa” shed light on how colonialism continues to manifest in the present. This can be observed through the German government’s pride in renaming colonial figures, linguistic distinctions between “expats” and “immigrants,” and the portrayal of Cowboys versus Native Americans in games, and so on. The concept of the “other” remains historically situated and perpetuates into the present day. This brought to mind the differential approach of the German government towards its colonial history compared to its handling of the history related to Hitler and the Nazi regime.

Evidently, the German government has been complex and sluggish in addressing its colonial past, while it has been swift and efficient in handling issues related to the Nazi regime in the post-war period. I believe that the German government’s expeditious response to the Nazi problem was due to the country’s defeat in World War II, as Germany, as a defeated nation, was obliged to confront other victorious countries. … In contrast, most African countries were historically divided and colonized, leaving them in a position of powerlessness. Hence, after Germany gradually regained power following the resolution of the Nazi problem, it did not feel the need to be accountable to the still vulnerable African communities. Consequently, the pride associated with exerting power over the “other” continues to persist in German society today.

History is not confined to the past; it remains embedded in the present. The handling of the Nazi problem serves as an example to illustrate that if the German government desires, it possesses the capability to swiftly address the complexities involved in matters such as documentation and community facilities. The government’s negligence in this regard clearly reveals its attitude of romanticizing the conquest of colonised African Societies such as Togo.

Our guide Tayan talks to students about the politics of (street) naming.

Man Wai: After group dinner, I have a walk alone near the restaurant because I was so full. The sky suddenly rained. Really, suddenly, with no prediction. The weather here is interesting. Today is sunny, windy and sometimes rainy. So I sat outside the table of the restaurant. I stared at people who passed the road. They looked so calm no matter it was suddenly raining or the traffic light has turned red from green. An accident happened and I found that German is cold outside and hot inside. An elderly man went off the bus but there was a barrier in front of the exit door, so he tried to move it. However, he unintentionally dropped it down and it unfortunately crushed the foot of a man. He felt so much pain because he immediately sat on the chair near me. The man said something but I didn’t understand German. Both of their faces were serious and I thought they were going to fight with each other. Nevertheless, the elderly man got closer to the younger man, seeming like to look after his injury. The man didn’t say anything, rather, he waved his hand to show he was alright. Then he patted the elderly’s shoulder twice and left with his wife and daughter. Less to none conversation but so warm. In these few days, I felt German looked grimmer than others. They had no smile. After today, I knew the kindness of them though they still didn’t show their smile here.

Enjoying Turkish food in Kreuzberg.

Day 6: Walking along the Berlin Wall

Sze Wing: Walking along the corridor that once symbolized division, I felt and experienced the weight of history with my own footsteps. In the history class of my secondary school, the picture of the “The socialist fraternal kiss” was often quoted and used to illustrate the historical situation at that time. I still remember the shocked reactions of my classmates and what my teacher said, as he told us that we must go to the Berlin Wall sometime and see the graffiti on the wall because it is meaningful for all of us. I never imagined that a few years later, I would have this precious opportunity. When I arrived, all the tourists ran to the same piece of graffiti to take a picture, which shows its symbolism and unexpected tourism value. Besides, I also saw a number of artists depicting or colouring other walls. The themes of these walls varied from satirizing current affairs, artistic expression to cultural propaganda. It was like an art platform for artists to express their voices, showing their freedom and making me feel more tolerance of the city. I passed by a coffee shop and was particularly impressed by the slogan, “if you are racist, sexist, homophobic or an asshole, don’t come in.” The value of respect is embedded in this quote. I love it so much and it makes me realize that the vitality of this city lies in its openness to “all kinds of people”.

At Eastside Gallery: Local artist Elisabetta explains the difference between street art and the museumification of art.

Contested spaces of belonging: Osman Kalin’s treehouse in the former borderland.

Crossing from East to West Berlin on Oberbaumbruecke.

Zhiyuan: The Checkpoint Charlie Museum is exhibited in a way very similar to a cabinet of curiosities, a treasure box of the history of divided Berlin, and, in part, human rights events in other countries. Particularly, the labels and panels are written in the four languages of the countries that shared Berlin after WWII: English, French, German, and Russian. In front of the models and photos demonstrating how people crossed the Berlin Wall to West Berlin are modified car engines, furniture used as hiding spaces, fake IDs, and other tactics for escaping. It seems to me that the allure of the museum is not just about learning about an “important history.” I’d rather say the stories satisfy the imagination of a rebellious desire for freedom and democracy in contemporary Western ideology, which builds the importance of this history and what the wall symbolizes today.

A small step for Zhiyuan, a struggle for generations: Stepping over the former Wall in Berlin.

Street art in Kreuzberg.

Despite how much we discussed it, I remained quite confused about the differences between the East and West parts of current Berlin. On the first day’s history tour, I noticed that the historical legacies were left in Soviet East Berlin, although they seem of great importance today for art spaces and tourism. During our long walk to trace the wall, the concepts of East/West Berlin were indeed materialized in our perception of the space, especially the turns that caused us to lose our sense of direction. In walking, we were getting to know the city and its history. Moreover, the conflicts between new urban planning and the memorial legacy appeared intriguing: the wall’s mark was honestly disappearing when pedestrian boundaries or parking lots intervened.

On a bridge between East and West Berlin.

Day 7: Queer Berlin and Housing Politics

Tim: We went with our guide Walid on a “Queer Berlin” Tour leading us from Friedrichshain, to Kreuzberg and Schoeneberg in West Berlin. The students learned about the long history of Berlin as a queer space starting in the 1920s, and the various waves of repression, persecution, and liberation. Walid is an interesting person, a gay man of color, coming from London with a South Asian Muslim background, a heavy metal guitarist living for over 20 years in Berlin and a self-proclaimed “prude”. He loves to talk about how various political disruptions enabled free spaces and how the queer movement overlaps with migrant and leftist spaces, and the techno scene in Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg. We ended in Schoeneberg, a more middle-class area near Kurfuerstendamm in the west, the visible gay center of Berlin: Rainbow flags, leather shops, and clubs and bars dominate a few blocks and even in the early afternoon gay men are very visible.

Our guide Wadli shows us the Berghain, famous club and queer hotspot in Friedrichshain.

In the afternoon we meet Tobias, from the Enteignet Deutsche Wohnen movement, aiming to reclaim public housing apartments (250,000 of them) from private investors using the German constitutional law. Tobias is in his twenties, a young, dressed in black, blond, German activist. He explains the rather complicated procedures and the grassroots efforts to get 300,000 signatures and over 1 million votes. The housing issues of Berlin, the limited space, affordability, and ongoing pressure on its citizens resonates with us from Hong Kong, making us wonder: Who owns the city? Who has a right to the city?

Who owns the city? Tobias tells us about the efforts to reclaim public housing in Berlin.

Xiaohan: In the queer tour that we did today, our tour guide mentioned that the fall of berlin wall actually created a political vacuum that resulted in a number of techno clubs and homosexual bars that we see today. He said that “Berlin need a wall to become rock and roll again”. Tim asked us to think about the meaning of this, which is twofold. The first part is about how the political vacuum created relief and how the tension that the cold war may break out at any time suddenly get relieved overnight. The second layer is about how as a Berliner who has never actually experienced Berlin Wall, he doesn’t fully comprehend the trauma and pain the wall brought before 1989. While tension and relief are good things, they are largely unequally built on the sufferings of the East Berliners rather than the west.

Zhiyuan: I realized how prominent the queer scene in Berlin is and how tourism has also developed around such sightseeing. The guide, being part of the queer community himself, with very rich life stories and a British accent, also offers an oral history of queer life in Berlin beyond the locations that are considered important for the LGBTQ+ community in terms of social life, cultural formation, etc. “It’s so boring to be gay or lesbian now, it’s just normal, but wait, I thought we were special?” said the guide repeatedly about the current situation of the queer community in Berlin. Walking in the quiet, and even a bit slumped neighbourhood in Schoneberg during daytime, the glory of history seems to really be in the past. What’s left are mostly places for gay social life: many rainbow bars and restaurants, one LGBTQ+ bookstore, and a sex shop. Absorbed in the “inclusiveness” of the culture here, I find “boring” an intriguing term from him, describing what is supposedly the victory of the demands of the marginalized community. However, the world as we know it still struggles intensely with the rights and stigmatization of queers, outside the bubble of Berlin or the bubble of how our guide lives and perceives.

Hei Man: During our conversation with one of the protestors involved in the Berlin rent protest today, we discussed the underlying causes of the protest. At the core of the issue lies the question of how housing should be understood. Is housing merely a commodity within the housing market, or is it a fundamental necessity akin to water? The answer to this question has implications for the commodification of housing. From my perspective, housing is a necessity. While it may not directly result in immediate fatality if one lacks housing, it is widely acknowledged in modern society that we all require shelter for habitation. Housing is not a luxury but a fundamental determinant of individuals’ living standards. The commodification and speculative trading of housing make it increasingly difficult for low-income individuals to obtain suitable living environments.

This situation is also prevalent in Hong Kong, which serves as a quintessential example of a housing market driven by speculation. The exorbitant property prices in Hong Kong force the majority of its population to toil for a lifetime to acquire even a tiny living space. For young people, this aspiration becomes an unattainable dream.

Day 8: Visiting the Former Airport Tempelhof

Tim: We were guided by Julia and Mira–two Anthropology PhD students at Humboldt University–who showed us around the Tempelhofer Feld: The former airport in the middle of the city, now a public recreational space, start-up space, and a site of refugee housing. We first visit City Lab, a publicly funded developer of digital solutions to urban planning from trees to traffic. Juxtaposing the old interior and straight lines of the airport terminal, built by the Nazis, the ‘lab’ is presenting futuristic planning in neon colors, diagonals, screens. Offering a different vision of urban space, the lab interestingly stands in the tradition of German planning.

Berlin PhD students Julia and Mira introduce us to Tempelhofer Feld, the former Berlin airport now a public park.

Hui: Tempelhofer Feld Park is my favourite place in this Berlin field trip. When we first entered the park, I was amazed by the grassland and blue sky. It was so beautiful and relaxing. Our large group of 22 people even found big tables where we could have lunch together. Other visitors were also enjoying their gatherings. After lunch, my friends and I ran to the deckchairs right next to the lunch area. I believe they were provided by the restaurant, and it was so comfortable to sit there and have my drink. The sun was warm, and I even slept on the grass. It was incredibly relaxing.

Lunch break at Tempelhofer Feld.

Later, Mira and Julia led us further into the park, and I was stunned by its massive size. I couldn’t even see the end of it. On the former runway, there were people with their dogs, while some were running, cycling, and roller skating. So I decided to set myself free and start running on it too. The feeling of the wind and the warmth of the sun was unforgettable. This is the thing and feeling that can hardly be experienced in Hong Kong.

So much space: Walking the former runway.

Being a local Hong Kong person, it is very hard for me to imagine an old airport being converted into a huge public space, instead of being developed into a commercial or residential area. This is a place where everyone can truly enjoy themselves. More importantly, it was a decision made by a public referendum. This related to my previous visit to the Berlin Exhibition at the Humboldt Forum, where I learnt that people living in the city have the right and ability to shape their living space.

Sitting in the grass, resting in the middle of Berlin.

Acknowledgments:

The field seminar would not have been possible without the tremendous support by Kathy Wong and Irene Chan, who took on most of the administrative and accounting duties. Thanks to Kathy’s initiative we were also able to secure additional support for our undergraduate students. I therefore want to gratefully acknowledge the generous funding by the UGC Funding Scheme for Global Learning & Experience Programmes.

I am especially thankful to all the people and interlocutors in Berlin who offered their time so generously to open a window into their world: Jingyang Yu for her insights into the Chinese community of Berlin; Nirit Bialer, Dekel and Nina Peretz from the Jewish Community of the Fraenkelufer Synagoge; Tobias Gralke from Deutsche Wohnen Enteignen; as well as Julia Schroeder and Mira Wallis for taking us to Tempelhofer Feld.