Artistic déjà vus

Photography has always been part of her life. At nine, she was given her first camera by her father. In high school, she photographed for the school newspaper. At 18, she went to study painting at the University of Delaware for two years, and after that moved to New York in 1971 to study fashion design. Later, the photographer Philippe Halsman, who taught the Psychological Portraiture class she took in 1973, encouraged her to study photography as her real métier.

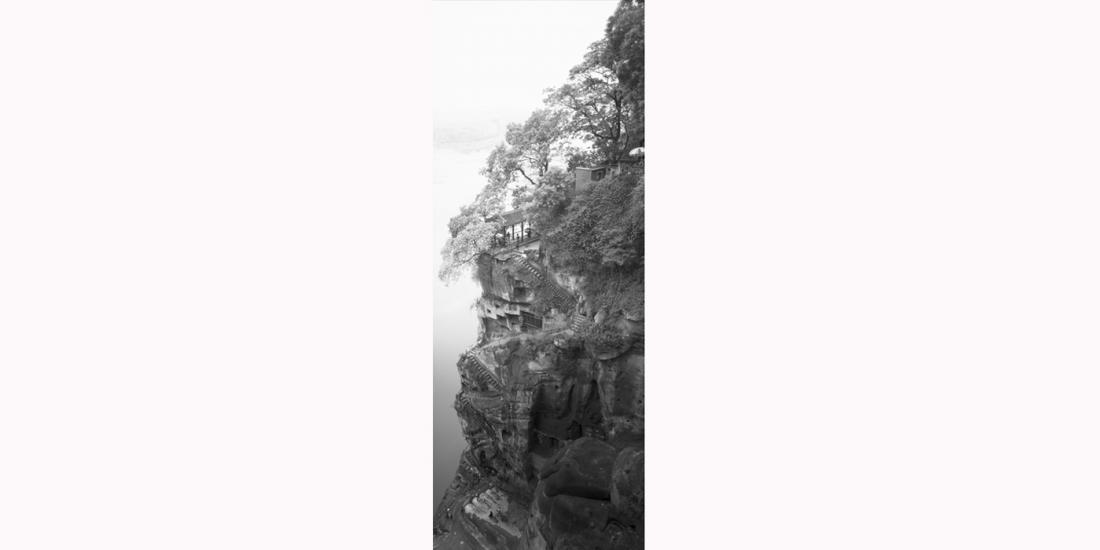

At Yale, in 1980, during her graduate study, she took a class in Chinese painting from the Ming dynasty with the art historian Richard Barnhart. Intimidated by her lack of knowledge of the subject, she asked the professor if she could drop the class. Rejected by Barnhart on the grounds that inputs from students of a variety of subjects are invaluable, she stuck it out. Her class visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they closely examined Tang and Ming dynasty scrolls from the Crawford collection. When she saw paintings of the karst formations, she wondered why the painters made up such fantastical mountains. But she was told that these mountains were in fact real. It sealed the moment when she decided she needed to see the unique landscape of the Li River for herself.

Graces of the gods

In 1984, walking around West Lake in Hangzhou, she set up her camera to photograph a ladder set next to a tree for autumn pruning. At that time, due to technical limitations, she could only take 10 pictures a day. It was still morning, so she was careful and only exposed one piece of film. Throughout the remainder of her nine-month journey, she would think of this picture and wish she had made an additional frame, as she worried that at the last moment before she exposed it, someone had walked in front of the lens. The ladder was one of her photographs of China that John Szarkowski, director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, chose for the museum’s collection.

Twirling the lotus

When she returned to Hangzhou in 1995, it was the rainy season. The light was flat, so she moved in close to the lotus. The stems of the lotus were like calligraphy, drawing another language across the place. A decade later, this self-contained, luminous, tranquil world would offer solace. In 2018, to honour her late mother, and searching for her spirit, Conner looked down into the water at the sky to photograph the lotus.

In winter, with their roots still attached to the dying stems, lotus leaves can melt parts of the ice. “They looked like chalk sketches. It was a world so cold, but very beautiful. I had to ‘draw’ it—I think of my photographs as a kind of drawing,” she says.

During the pandemic, Conner started making circular pictures. “It was a strange, unprecedented time, with no beginning and end—like the circle. When forming a narrative, often it needs to be short and quite specific. Or, at times, a longer story; and sometimes, you need the sublime and infinite.”

As a veteran artist, what advice does she have for students here? “It is good to have a trajectory, but it’s also important to be open for other things to happen. If you are distracted and are really interested in something else, you have to be unafraid to follow that other direction through.” Her own artistic journey, eventually landing on photography after following many other paths, offers living proof.

CUHK in Focus

By Amy Li

Photos by Keith Hiro

[Click here to visit Ms. Lois Conner's webpage]