The shopfront of a Starbucks in Lijiang, bearing a phono-semantic Naxi translation of its name at the top of the plaque, engraved in Dongba (Photo by interviewee)

But despite its potential, it is still far from being in vernacular use. Being more of a token or an ornament, it could even be said to be in a state of living death. As with the Han characters, a different word often gets a different symbol in Dongba. Anyone who wants to use the script in everyday life will have to learn around 1,500 of its symbols, and the number goes up to 4,000 if they are to write the names of the many people, places and deities in the culture. This will take years of formal education, the impetus for which is simply lacking.

‘It’s taught as an elective for one or two hours a week, but it’s never going to get into the syllabus, because then the parents would be like, “My child is not going to get a job doing this”,’ Professor Poupard noted.

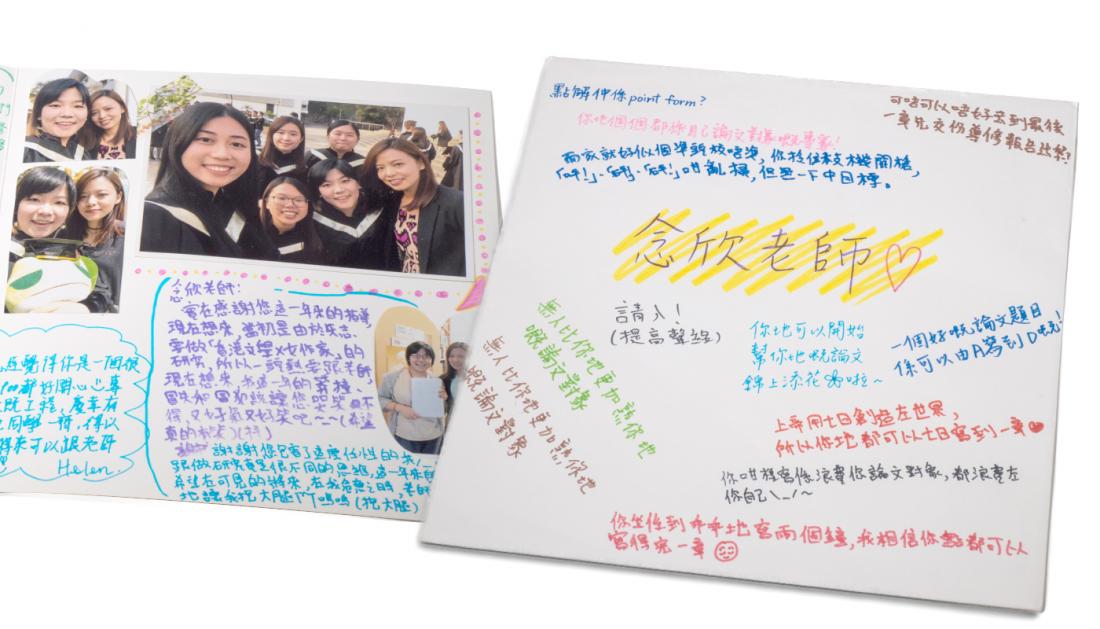

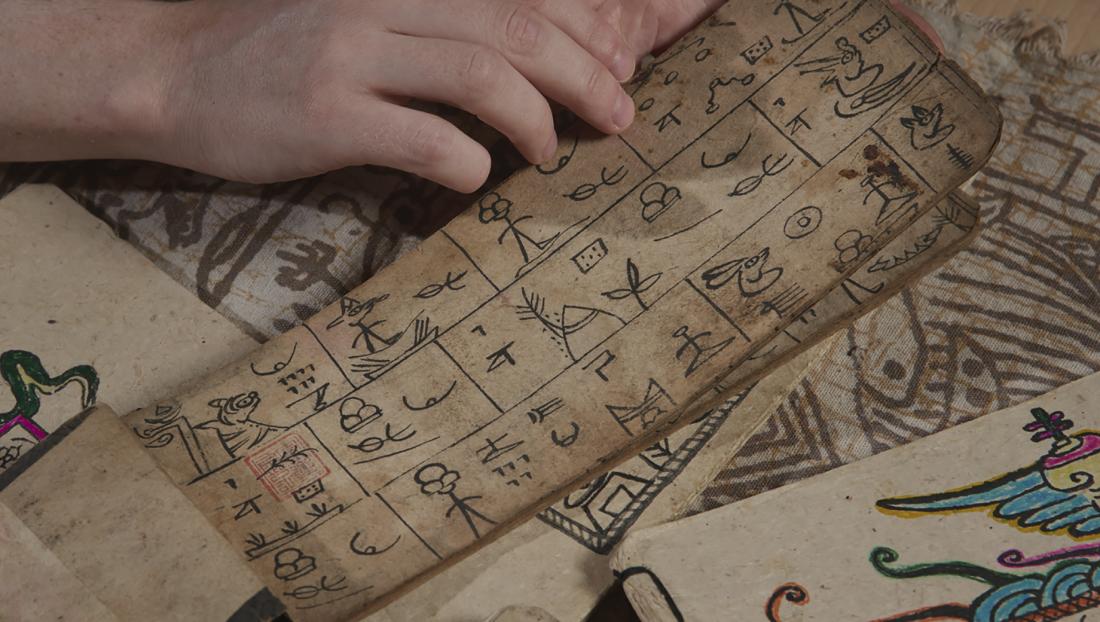

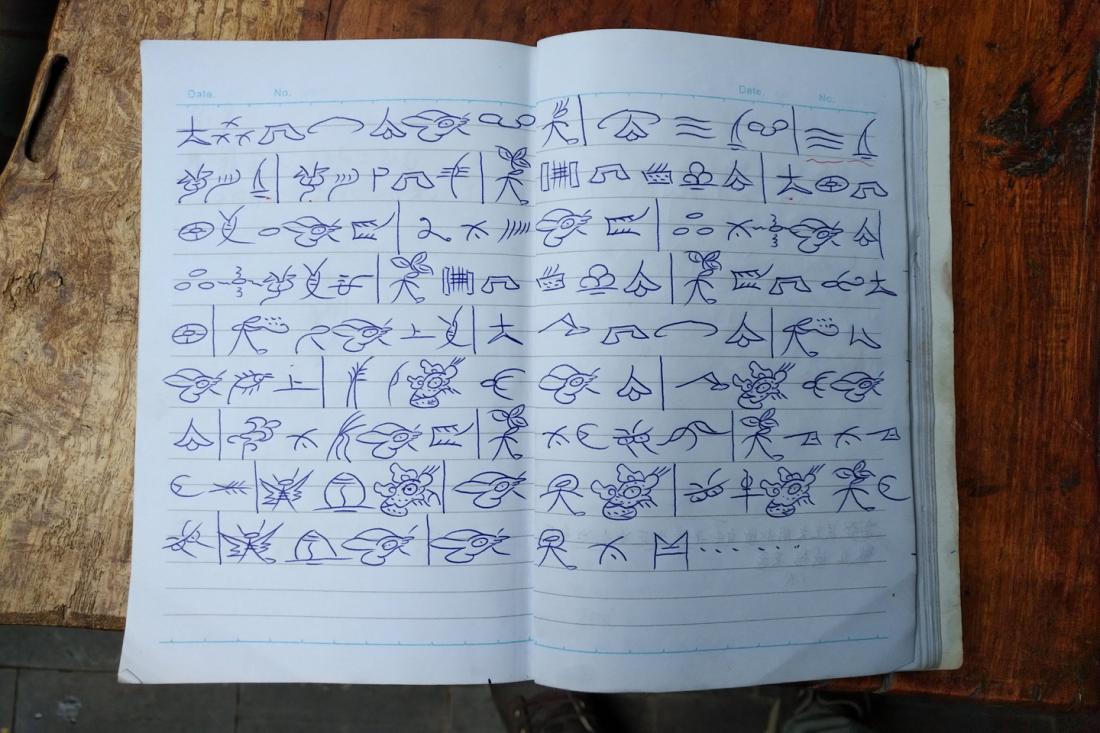

Having said that, there is certainly room for the script to be elevated. Moving aside his prized collection of sacred texts, Professor Poupard showed me a photo of a modern-day notebook belonging to a native Naxi student, inscribed with the lyrics of a popular song in a most graceful Dongba script. Perhaps this is what the writing system can aspire to be for now, a tool for self-expression, and to that end, Professor Poupard is going out of his way.

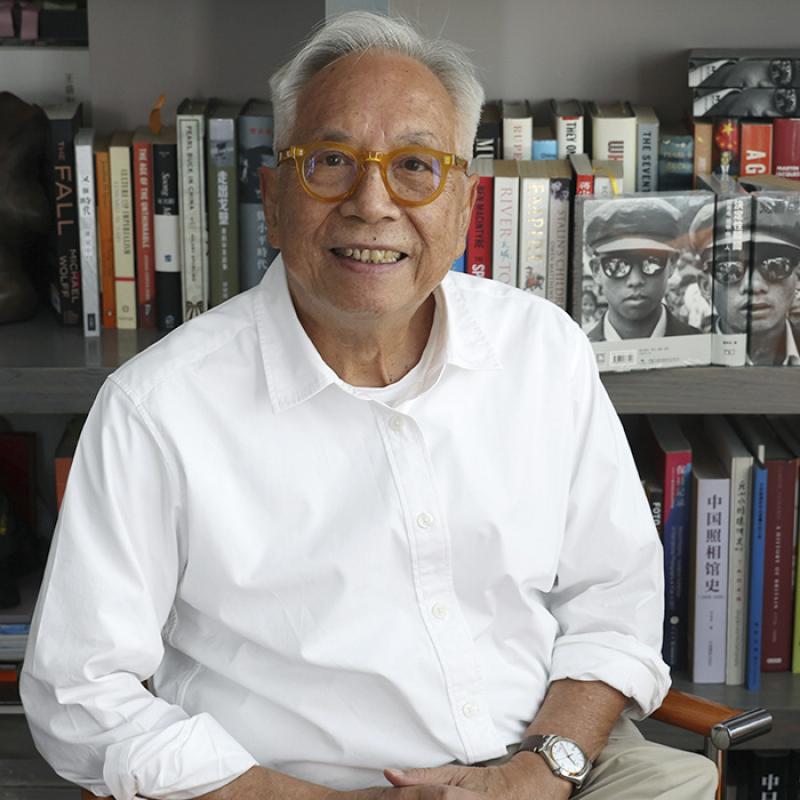

‘I wrote an article about revitalizing the script as a vernacular last year, and I decided that if I’m serious about this, I should reach out to a wider audience rather than just writing for a journal that only 10 people will read,’ he said with a laugh. And so he has teamed up with an exhibition centre in Lijiang to produce video lessons teaching the basics of the script while preparing for a public showcase in London of his British Academy-funded research, where he intends to have a dongba priest do some simple recitations and give visitors a taste of the script by demonstrating how to write their names with it. Ultimately, though, he thinks the script’s future comes down to whether there is a way to type it.

‘We need to be able to input it easily on modern devices, which means it needs to be encoded in Unicode,’ he said. ‘Hopefully this will happen at some point, and then we can get an input method, possibly a phonetic one.’

A local Naxi student's notebook with the lyrics of a popular song in Dongba (Photo by interviewee)

One might wonder why we should care if such a marginal writing system is alive and well. Apart from being a religious tool and inspiring arts and crafts locally and abroad with Ezra Pound using it in his Cantos, the script is in itself a cultural treasure trove. In the Dongba character for rherqngvlv , the word for the windy snow mountain watching over the Naxi, the summit is depicted with a mouth letting out a cry. Beyond being a neat artistic trick, the personification may well be a window into the way the Naxi view nature, one that is lost if the script is gone.

But at the end of the day, the love of the script or, indeed, any language is perhaps a love that needs no reason. It was this natural affinity for what is ‘different’, in his own word, that first got Professor Poupard into Mandarin, took him from York to Zhejiang after university and immersed him in a Dongba text for the first time during a summer trip to Lijiang. The same should go for all of us. There is after all something to be celebrated about the fall of Babel—the very fact that there is a diversity of languages and scripts—for it is these many fires, cropping up as far as in the Himalayas and as near as at home, feeble as they might be, that give the world its splendour.

CUHK UPDates

By jasonyuen@cuhkcontents

Photos by Keith Hiro